In light of recent social justice issues that have been brought to the eye of the public and to the eye of Loyola’s institution, The Greyhound had conversations with multiple Loyola students who have taken action on these issues this summer.

Savoy Adams ‘23 is a sociology major with a deep passion for addressing racism on campus, in Baltimore, and across the nation. Last month, Adams wrote a letter to Loyola’s president, Rev. Brian F. Linnane S.J., the cabinet, and the board of trustees that outlines racism on campus and offers actionable items to address such culture. His letter can be found here. It acts as the basis for his forthcoming profile.

Savoy Adams is a native of Baltimore. He’s also a member of the Loyola community, though this latter part of his identity did not formulate without substantial consideration of his academic options. While applying to colleges, he compared the experiences he could have at a predominantly white institution (PWI), like Loyola, to those he could have at a historically black college or university (HBCU).

Prior to committing to Loyola, Adams had conversations with Dr. Will Romani, the renowned entrepreneur in residence at Loyola’s Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. When asked about his passions, Adams answered with specifics: from mass incarceration to policing, he explained his desire to analyze systemic racism from its core to its most lasting impacts. Adams was then connected with Rev. Tim Brown, S.J., an associate professor of law and responsibility at Loyola’s Sellinger School of Business. These introductions were notably impactful on Adams’ decision to attend Loyola, a PWI that would bring about new challenges that were different than those he faced during previous academic experiences.

Adams’ education before college had yielded some notable opportunities to learn about the “hows” and “whys” of his immediate Baltimore community. As a high school sophomore, Adams was accepted into and participated in the Elijah Cummings Youth Program, an elite leadership fellowship for high school students in Baltimore.

Part of the program included traveling to Israel for one month to better understand the connection between the Black and Jewish communities. Adams was able to “put my money where my mouth is [in his activism], and do this on an international level.”

Upon his return, this understanding was then applied to Park Heights, Pikesville, and other communities in Baltimore. In both the Black and Jewish communities there, Adams said:

“There’s almost a complete divide of resources. You can see it so visually, there’s a big difference between the two. And also there’s a race difference. That’s an even bigger issue.”

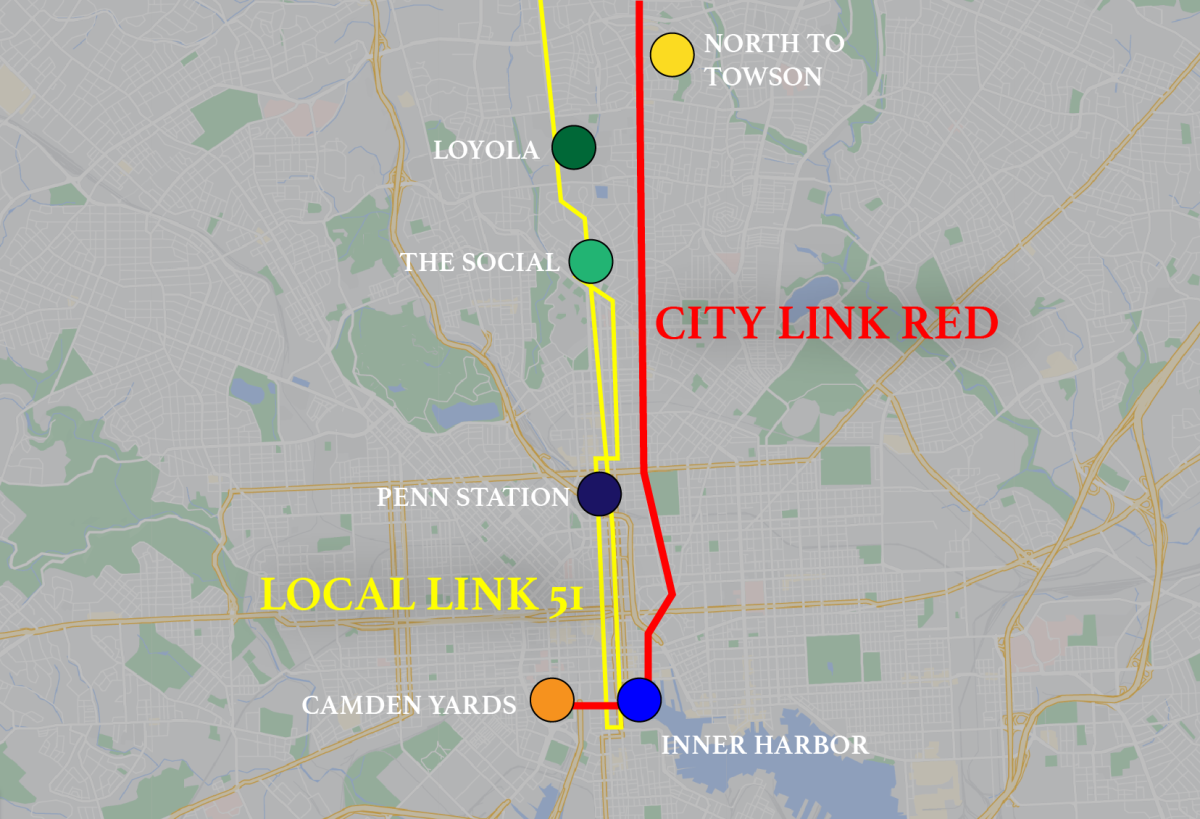

Much like the stark difference between Loyola and its surrounding community, Adams found that the Black and Jewish communities were both close-knit within themselves, and also close in proximity, though they had little to no connection.

Adams said his inspiration comes from “the events that have transpired in my life that made me want to set the tone, and be different, and view that new path to really address the system.”

Realities and experiences, such as those he was confronted with when working with Israeli students to share and understand the differences between American and Israeli cultures, have allowed him to see the bigger picture and understand deeper into institutional issues.

This inspiration drove Adams to take further action on campus. As a first-year, Adams observed how Messina and other programs at Loyola talked about the ways in which students could “safely” interact with the city, which he found off-putting.

“Yes, you want students to be safe, but when you tell students to do it from this point of view, and to not go to this area because there’s people who look like me who occupy those areas, then, again, it’s like, ‘they’re dangerous’ and [the point of view] criminalizes those areas,” he said, further explaining the damage such sentiments can create when introduced so early in a Loyola student’s academic career.

The solution? Educate students on the area they’re being advised to avoid and explain why it’s like that.

“These people didn’t just do these things overnight,” Adams said. “Or, they didn’t become impoverished overnight. This is so institutionalized. So I think a big thing would be addressing the system and explaining sort of why. Not the idea of looking at poverty and [saying], ‘Oh i feel bad for them,’ but showing them why.”

Adams’ desire to expand education and information beyond what Loyola’s culture has normalized manifested itself in many different ways.

An example of Adams’ efforts is in his work on a radio show for Loyola’s station, WLOY. After starting out as a DJ, Adams wanted to connect the radio to Baltimore and his interests within the city. He ended up reviving an older show the station used to put on, titled “Both Feet In.” The show aims to “normalize homelessness and not make it such a criminalized thing.”

Adams said, “A lot of times, you see homeless individuals, and you think along the lines of drug abuse, alcohol, and it’s a mostly negative picture. Some people have been born into certain situations that they have no control of.”

The radio show has been used as a platform for people who are homeless to tell their stories and speak their truths about their experiences, and also as a means to share resources about what it’s like to experience homelessness.

Another effort seen through by Adams was the foundation of Addressing the System. This initiative was created by Adams and a friend during the spring 2020 semester. Despite being stunted when the University was never able to welcome its students back to campus, Addressing the System was still able to establish an Instagram profile. As a resident of Baltimore, Adams is able to experience the pandemic within the city from a first-person perspective. Adams felt the impact of COVID-19 on impoverished communities very deeply— the rates in Park Heights, he noted early on, were especially high.

Adams decided that starting a conversation about these rates and encouraging the continuation of education was an important thing to be done, and something that could be accomplished through his platform on Addressing the System.

Adams said, “I decided that we should host a virtual Zoom about how COVID-19 is affecting Black and Brown communities. It was a really nice turnout actually, people joined from all over, from where they were from, and I gave an inside look into what was happening in Baltimore, a breakdown of what that community looks like. Like yes, they [Park Heights] have the highest COVID-19 rates: [it is] predominantly Black, predominantly uneducated, a lot of food deserts, all these different issues.”

This remote conversation gave an opportunity to others at Loyola to share what they were doing to address these disparities in a time when they needed it most.

“[Addressing the System] is basically about systematic issues. The idea is that first we educate, and we can learn from that community in some way or another. And the next part would be action,” Adams said.

One action that has garnered significant social media attention within the Loyola community is Adams’ letter, which was posted to Addressing the System’s Instagram account on Aug. 23 and was shared widely within the community.

The letter, which addresses racism on campus through an analogy to Baltimore’s complex history and current reality of redlining, wasn’t written in a day. Rather, it became a summer project of Adams’, born out of his desire to become a better writer over the last few months. Adams looked to writing professor Dr. Lisa Zimmerelli for support, who helped him articulate his ideas before submitting his final product.

The more Adams worked on the piece, he became inspired to add context about himself and the issue at hand. Between cultivating his writing skills and providing thoughtful commentary on the events of this summer that encouraged such demands for a cultural shift at Loyola, from COVID-19 to to the killing of George Floyd, this letter was a huge project for Adams.

“It wasn’t just a weekend I decided to write,” he said. “It took time.”

Moving forward, Adams hopes that Addressing the System can allow its members to meet and have an open discussion about a specific issue within systemic racism. His goal is to expand student mindsets beyond fear by continuing to educate and normalize open conversations about the realities in surrounding communities.

To Adams, a divide between communities is created by telling students to steer clear of areas of Baltimore without explanation of the situation. This approach, under the guise of promoting safety, acts as a roadblock to change and prevents students from becoming authentically versed in different kinds of communities. In his eyes, it also deters students from learning about disparity, and how the history of the city can dictate what kind of lifestyle is led in a specific place. Addressing the System hopes to be a force against this.

Adams said, “When these people [Loyola students] go into their careers, is Loyola setting them up to be actually diverse individuals? And not just by having diverse friends, but being diverse in the communities they work and live in?”

Adams also spoke on a recurring concern that students of color are being “quartered off” to the Center for Intercultural Engagement (CIE) and ALANA Services. According to Adams, this relatively new space has been virtually the only place students of color can feel comfortable living their lives and having discussions on these issues. As proposed in his letter, this normalized culture is a manifestation of redlining within the Loyola community.

“If [Black, Indigenous, and people of color culture] is not embedded throughout the campus like the white culture is, it’s not doing anything. It’s like you’re half-stepping it, and you’re forcing students of color to almost assimilate more so into white culture and not letting them bring their own,” he said.

Adams hopes that Loyola wants genuine diversity and inclusion but hasn’t yet figured out an effective way to implement it.

So, what now? Adams believes that these efforts and conversations should be more about what is going on in Baltimore directly, not just on what Loyola is “doing” for the city.

He is calling on Loyola to deeply consider the proposed solutions he outlined in his letter. Adams wants to see Loyola, as an institution, make changes that have a deeper impact on students through their discourse and curriculum.

“[I want to] see the school really make the changes that they identify with, you know, in the Jesuit tradition. I think changing [the name of] Flannery O’Connor [residence hall] was important, but a small gesture to a certain degree, because that wouldn’t affect me. That’s not a systematic change that would affect me. If you were to hire maybe 20 more Black professors, that would affect me and that would actually do something to the population of the school,” Adams said.

Modifications to the bias reporting system wouldn’t hurt, either, in Adams’ perspective. To him, the system puts too much of a burden on the victim and the repercussions of having a bias report filed don’t seem consistent. This inconsistency only invalidates the system further.

Adams explained that Loyola needs to be aware of the impact it has on all of Baltimore. In Adams’ view, there are two Baltimores: one has the resources, and the other has the people of the city that those resources should cater to. But, really, there’s an ideal Baltimore, where those resources would be distributed evenly.

“We have some of the best hospitals in the country. It’s not available to everyone. We have some of the best schools in the country. It’s not available to everyone,” Adams said. In situations like these, the University could be doing more against the already-existing divide between the two realities of Baltimore, as proposed by Adams.

And it is with these hopes and calls to action that Adams goes on to continue his own education, and plays a role in that of others.

Like Adams, many students at Loyola are stepping up to address inequity on campus and in the Baltimore community. For more profiles of those making big changes, keep checking back with The Greyhound.