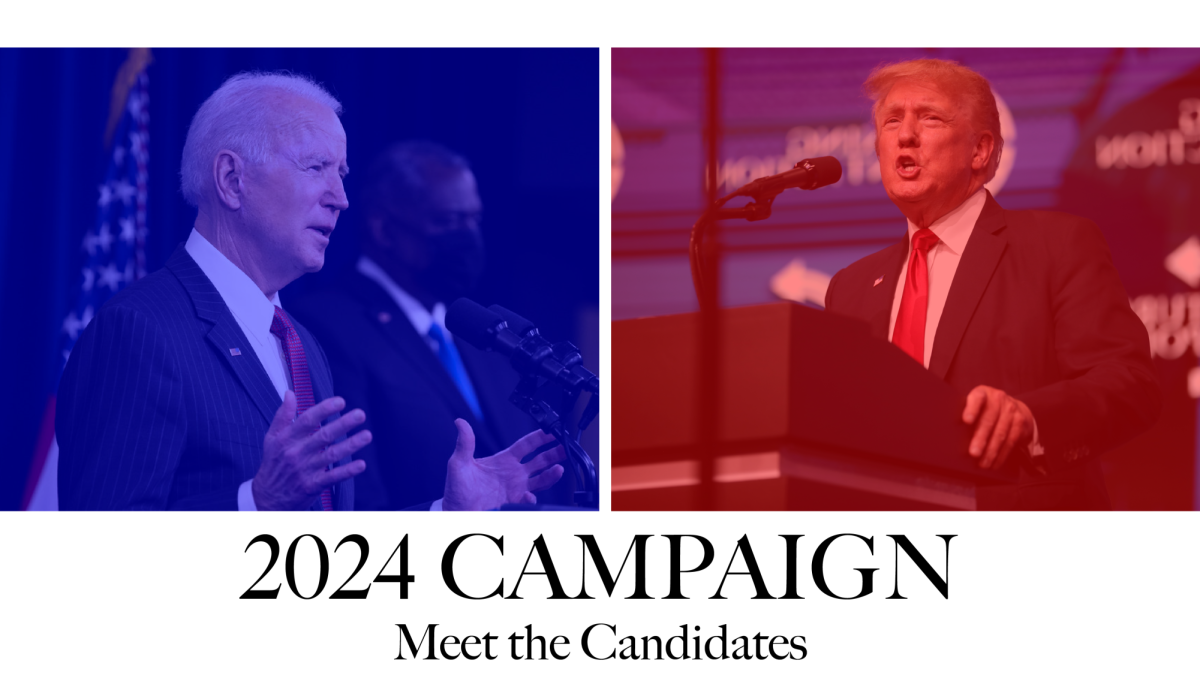

I should perhaps preface all of this with an admittance of my personal political bias; I am a registered Independent in the State of Maryland, and am therefore not officially part of any structured political faction. As to how that affects the way my opinion should be perceived, that is for the reader to decide.

Last Tuesday, less than half of registered Americans went to voting booths around the country to determine who would represent them, their community, and their state. One major aspect of voting results that often goes unnoticed by many individuals, is realizing whether the way one is voting is actually going to benefit one, or is going to achieve the desired goal. In essence, why one is voting the way one does. Is it because one believes that the specific candidate supports one’s interests, that their party is more aligned with one’s personal vision of the direction you want the country to take? Or the opposite, which many claim, perhaps with too much emphasis, may have been one of the reasons for the Midterm election results: Opposing the reigning party as a matter of voter disobedience, more to send a message to those in power, beyond anything else.

One can question the validity of these reasons, but I personally find all of them, as well as others, as acceptable motivation for the check on the ballot. That is not the concern here.

What is a concern is how the then elected officials interpret how they should react to both voter turnout and voter decisions. A large majority of the country identifies as either Democrat or Republican, but quite unlikely is the notion that they support every action their chosen party takes.

There are many analyses being offered of why the Democrats did so poorly last Tuesday. There are notions that it was a referendum of the Obama Administration, that it was a result of new wave Republicanism, that voters were acting reactionary. All these explanations, and many more, have both justifications and flaws, but the fact that there are so many is the true fundamental problem. Voting, above all else, has been considered to be the most effective way of having a voice in a democracy. But if everyone is speaking a different language, the translation of that voice can be used to say anything. Voters who attended the polls last Tuesday had their reasons for voting the way they did, and it would be incredibly unreasonable to say that the widespread success of the Republicans was not motivated, in part, as a result of distrust and dissatisfaction with the actions of the Obama Administration, as well as a failure of the Democrats to mobilize their base.

There may well be a number of voters that genuinely do support the specific candidate they elected, because of their policies and promises, but these voices are interpreted as having a meaning on a national trend level by some analysts, a historical one by others, and so many other possible explanations, rather than the one expressed by the individual voter. Yet, it proves to be incredibly difficult, by both Parties and their newly elected candidates, to accurately divine what their constituency wants when it votes in support of them; Too often, the result is split. Obviously it is impossible to please every voter who supports the candidate, but it seems that even the existence of so many explanations for why citizens vote the way they do is troubling for how well they may be represented by both candidates and Parties, across the political spectrum.

There is no simple solution to this problem. At the state of community levels, voters can often decide on laws or policies directly, allowing a much more accurate result to ascertained. This is generally impractical on the national level for a variety of reasons, mainly regarding significant differences between population density and regional interests. One can delve into the benefits and conflicts of having more political parties, the necessity of political parties themselves, the essence of Democracy as a form of government and the meaning of Life, the Universe, and everything. But as many have said in the past, almost to an understandably excessive amount, the first step in addressing a problem is admitting that one exists. As to its magnitude or importance, that is always up to interpretation; But that argument, in itself, is evidence to the aforementioned issue.