Flor Paniagua-Peart was four years old when she moved from her birthplace of Argentina to the United States. As a toddler, valuing differences in culture and communities became second nature to the now-rising senior, and with time, so did addressing the unique social problems present within each kind of community. Utilizing medicine as her avenue for change, Paniagua-Peart is currently pursuing a degree in biology and writing and plans to enroll in a master’s program for nursing post-graduation. She chose her career path out of a moral obligation to serve the underrepresented, specifically the Latinx community.

Paniagua-Peart loves Baltimore. She loves its people, its culture, and its food. A significant portion of Paniagua-Peart’s energy is dedicated to Health Outreach Baltimore, an advocacy organization at Loyola that supports and empowers patients at Mercy Hospital. Here, she especially enjoys working with new mothers, providing assistance with breastfeeding and ensuring newborns have adequate places to sleep. Aside from her life as an up-and-coming young medical professional, Paniagua-Peart loves trying Baltimore’s restaurants with her friends, and traveling: two activities, typically considered leisure, that further extend her understanding of other cultures, traditions, and communities.

Loyola, too, is its own form of community. And like any other, the University has cultural norms that shape its values, actions, and reputation. It comes as no surprise that Paniagua-Peart found herself on the frontlines of Loyola’s chapter of the Do Better Campaign, a nationally-acknowledged organization asking colleges and universities to address gender-based violence on their campuses and in their communities. The chapter, more commonly referred to as Do Better Loyola, launched this summer in response to a recent uptick in allegations of sexual violence on campus and in the surrounding community.

It began as a disturbing reality check via the Do Better Campaign’s official Instagram account. The first of what would be over 20 anonymous allegations linked to the University was posted on June 22. In 48 hours, one story became three, and by the end of June, that number tripled.

As the situation progressively became more alarming, Paniagua-Peart contacted the organization and asked what she could do to help amplify these stories and demand a response from Loyola itself. She was put in contact with five other women from Loyola with the same concerns. Acting quickly, the group launched Do Better Loyola’s Instagram account with intentions to expand into a larger organization with time.

“I knew I wanted to do more. I knew I wanted to use my voice and kind of amplify this need for change and do something more,” she said.

Soon thereafter, Paniagua-Peart and her fellow organizers began circulating a form with questions, gathering feedback, insight, and information from Loyola students and others in the community. The form concluded with a space to write what actions those affiliated with Loyola would like to see the University take moving forward.

Considering the responses to the form, Paniagua-Peart and her fellow organizers turned the feedback into a community-informed, official letter addressed to the president of the University, Rev. Brian F. Linnane, S.J. The letter included 22 action items for the University to consider, including investments made in trauma-informed training for community members and professionals, an expansion of resources at the Women’s Center, and a commitment to stronger communication of allegations when they surface within Loyola’s organizations. The letter was shared alongside a petition, which could be signed to signal support for the movement.

“I don’t want the letter to just be our five or six voices, you know, seeing these problems,” Paniagua-Peart said, explaining the thought process behind the form. “I want[ed] to include other people’s voices, other survivors, other allies, other parents, families, friends, faculty, as many voices as we could get, of what people are seeing, cause maybe there’s things that other people see that I have not seen.”

In addition to branching beyond the organizers’ input, Paniagua-Peart prioritized the need for sustainability. With so many ideas of what reform could look like at Loyola, including a student-organized petition calling for the dismissal of Loyola’s Title IX coordinator Katsura Kurita, Do Better Loyola centered their call to action around what they perceived as the most sustainable approaches.

“At the time, a lot was going on about Katsura and whether, you know, getting her fired was something we were going to include in the letter, but I think we were more focused on, okay, firing one person isn’t going to necessarily make change. We want to come from more of an angle that we need to dismantle a lot of the foundation of Loyola and Title IX,” she said.

In addition to making resources more widely available and accessible on campus, the organizers were committed to addressing recent Title IX regulations, ones that Paniagua-Peart fears will make the process for survivors more traumatizing. They called upon Loyola to not adopt such regulations, which include a ruling that frees colleges and universities from responding to sexual assault or harassment that takes place in off-campus settings.

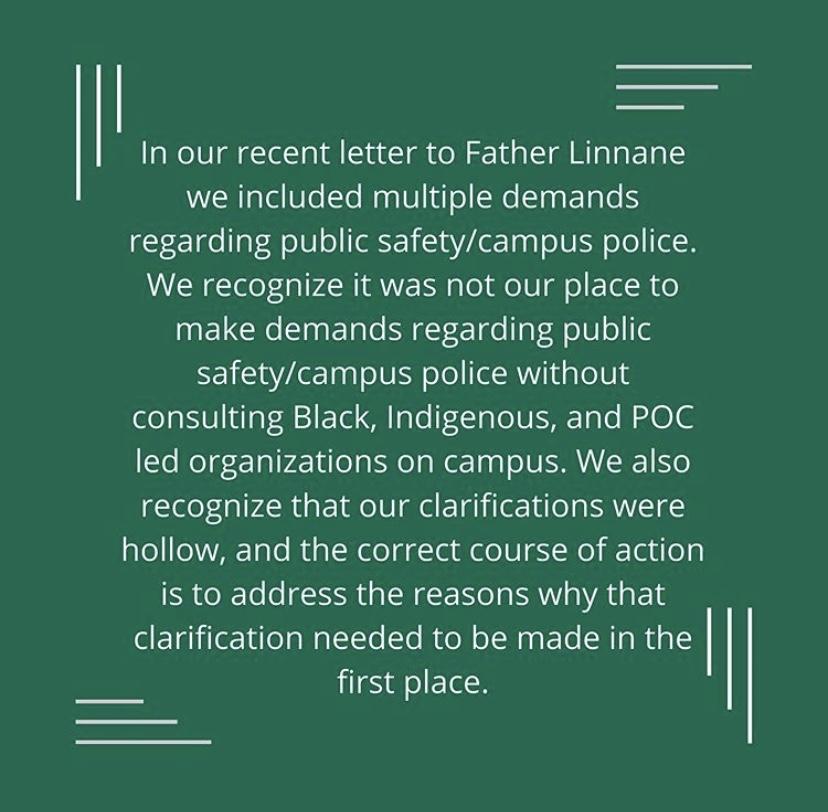

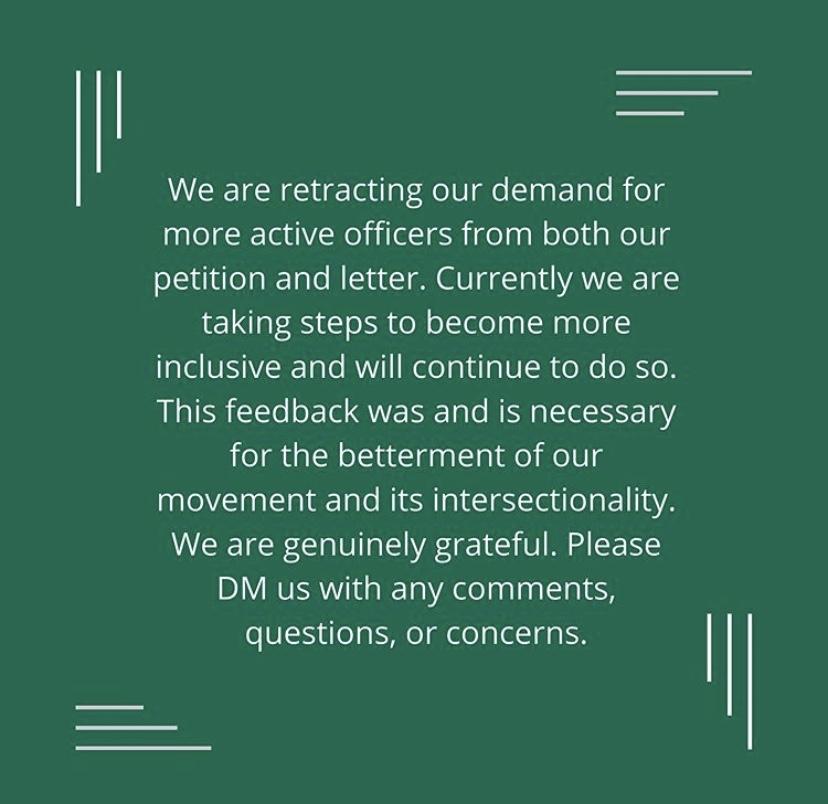

Though over 2,000 signatures of support were received, some community members took issue with a specific call within the proposal: the “greater presence” of campus safety officials at Loyola. While Do Better Loyola initially justified the request as a way to deter potential perpetrators, others viewed the call as a compromise to the safety of students of color on campus.

“Thank you for doing this,” one commenter said, underneath Do Better Loyola’s post of the letter. “I am a little hesitant to sign given the ask to expand Campus Police’s presence on campus. I worry that while this may make certain people feel safe, it will be at the expense of others (students of color, neighbors walking across campus, etc.). I am hopeful to discuss further with you all and again thanks for amplifying stories and your advocacy.”

The comment received 58 likes and was one of many with a similar sentiment. Three days later, on July 9, Do Better Loyola updated their calls to action, publicizing the news on Instagram.

“I think it was good that we started somewhere and published something somewhere. And I think that also led to us talking to so many faculty, to staff, to administrators. We talked to ALANA, we talked to the LGBTQ+ Experience, we talked to so many different clubs to try and get other people’s feedback, viewpoints on our issue, and their stance. So I think, while yes, some of our action items could’ve been adjusted and could’ve been perfected if we waited a little bit longer, I think publishing them the way that we did opened so many doors for us to be able to talk to other people which was really, really helpful.”

Though the original proposal required some reconsideration and alterations, Do Better Loyola’s request to meet with the president was honored, leading to a conversation among Paniagua-Peart, her fellow organizers, and Linnane at the end of July.

Paniagua-Peart viewed the conversation as one of many that need to come in order to enact sustainable change at Loyola.

“We want to keep this communication open,” she said. “We want to keep talking to him and members of this leadership team that he has for sexual assault and sexual violence to kind of continue expanding and making sure that we can hold them accountable for the things that they did say they want to do.”

During the meeting, the organizers stressed the need for Loyola to make a public statement on sexual assault and violence to prove their acknowledgement of the issue. The following day, on July 30, the Loyola community received a statement, via email, from the president.

In addition to citing other preventative resources against sexual violence, the statement provided eight actionable items the University plans to take moving forward:

- Conducting a comprehensive review of the University’s Title IX policies and processes,

- Hiring an additional full-time Title IX professional,

- Establishing Title IX intake officers,

- Surveying students about their experiences with Title IX at Loyola,

- Establishing an advisory board of students,

- Reconvening the coordinated community response team (CCRT),

- Reviewing and improving training for certain groups, including those in the department of public safety and mandated reporters across the University,

- Rewriting the mission statement at the Women’s Center to be inclusive of all gender identities.

Paniagua-Peart viewed the email as a “good start.” Though from her perspective, the statement failed to acknowledge a major aspect of the issue: the outpouring of allegations that began this movement in the first place.

“We asked for something a little bit more… I guess openness that he or the University is aware of the Instagram account and has read the stories, which are things that they said in their meeting— that they have read the stories, they read our letter, they read all the action items that we asked for. So we wanted that to be a little more transparent with his statement,” she said.

The conversation and subsequent statement marked a potential shift in the University’s dialogue regarding sexual violence that Paniagua-Peart hadn’t seen in her prior experiences at Loyola. Do Better Loyola has allowed her to connect with faculty and professors, too, some of whom didn’t know that sexual violence was such a large issue on campus.

“When you see an issue or you see a problem in a certain community, you might feel like you’re the only one who sees that problem, and I think I felt a lot of that with sexual violence. I felt like no one else on campus was noticing that this is an issue. That brought a lot of frustration,” she said. “But, I think the more I sat down and talked with other people, faculty, and staff and administrators, I was able to realize how much support I had.”

A talented community-builder, Paniagua-Peart cited two major recommendations for enacting change within an institution: find those already doing the work, and join them, and educate oneself before joining the action.

“I’ve always believed knowledge is power, and I think the more you know about an issue and the more you look at different perspectives and read as much as you can about it, I feel like the better it is,” she said.

In addition to conducting her own research via the internet, academic discourse, and through conversations with those of different perspectives and experiences, Paniagua-Peart recommends memoirs: “It feels like you’re with them,” she said, explaining her gravitation toward the genre. Specifically, she recommends “Hunger” by Roxane Gay, a memoir about womanhood in America, sexual assault, body image, and fetishizing relationships with food.

“I think it’s the most intimate book I’ve ever read. It feels like you’re sitting next to her while she’s talking to you about this,” she said.

Through what she describes as a moral obligation to serve others and empower the underrepresented, Paniagua-Peart has found her power in more places than one. Through culture, conversation, and community convening, she’s prepared to keep fighting for change: at Loyola, in medicine, and beyond.

For more profiles on student changemakers at Loyola, keep up-to-date with The Greyhound.