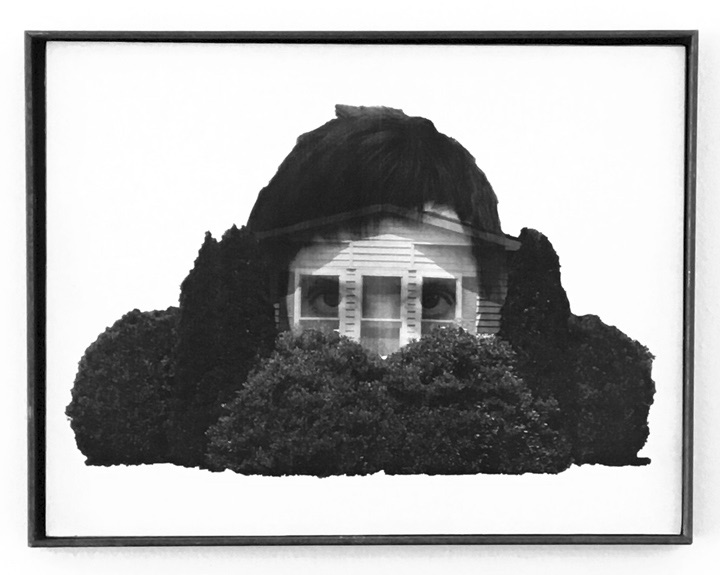

On Thursday, Jan. 30, Amy Ritter, the artist of the latest Julio Fine Arts Gallery exhibit “Built-in,” gave her artist talk regarding her career thus far, the overarching purpose of her body of work, and the significance that “Built-in” has to her personally. The exhibition, which closed on Friday, Feb. 7, consisted of 13 pieces of “photographic windows, street maps, and sculpture.” The materials Ritter used are taken directly from the types of materials used to build mobile homes, such as cinder blocks, OSB plywood, and steel.

Ritter explained that structures in mobile home parks, or MHPs, aren’t as feasibly mobile as their title implies. The cost to load up an entire “mobile” home onto a truck – not to mention the risk of damage in uprooting homes that have been in place for decades in some cases – is far too expensive in comparison to the amount paid to rent the lot in the park. According to Ritter’s experience, MHP residents are often uneasy and wary about anyone intently surveying their homes because of the fear that their home may unknowingly not be up to the code of the park. For her body of art, Ritter found herself pushing the social and physical boundaries of the park.

Ritter openly shared that she grew up in a mobile home park called Li’l Wolf in Orefield, Pennsylvania with major highway 76 running through the property of the park. At the beginning of her talk, she acknowledged her father sitting in the middle section of the McManus Theater audience, joking “I hope this isn’t too weird…” Ritter proceeded to show pictures she had taken of her, and her father’s, own home and neighborhood. Ritter has four numbered pieces in “Built-in” with the title “Li’l Wolf Window.”

Ritter naturally never minded where she grew up; she never even noticed the noise that came from the highway. She recalled the things that existed when she was younger that she never thought twice about, and nostalgically remarked, “Now I think about it all the time.”

Ritter’s own childhood exhibited significant parallels to the childhood of Sarah Smarsh, the author of this school year’s common text, “Heartland.” Although Smarsh grew up in rural Kansas, themes of invisible low-income communities’ contributions echo throughout her novel and Ritter’s artwork. Similarly to Smarsh, Ritter explained, “I haul cinder blocks everywhere. I work in construction. So if [the labor is] not for art, I’m still going back to construction… which goes to show that the hardest [laboring] people are often the poorest in America.”

Ritter created her first cinder block sculpture in 2015, in a decaying lot with broken cinder blocks strewn all over it. She decided to stack some of the blocks into a small wall without mortaring them together. Ritter then used wheatpaste on the blocks to blend a thinly printed photograph of a mobile home with a height near four feet tall, working with a scale similar to her own body, into the surface of the wall she created so that one could no longer be distinguished from the other. The piece Ritter constructed outside on the quad of Loyola’s main campus is of a similar idea: the cinder blocks this time broken on purpose and mortared together into an imperfect, short wall.

To obtain the photographs she prints and uses for her sculpture or installation pieces, Ritter would take short detours to mobile home parks near the locations she would travel to for work or otherwise. Her observation of MHPs became more of a hobby turned concentration of artwork. At the reception after her talk, Ritter opened up more. Regarding her confidence, Ritter profusely denied the assumption that wandering MHP communities becomes easier with experience. “No,” she said, “it does not get any easier. I think it gets harder every time.” To her, this difficulty has definitely coincided with the rapidly changing political climate since 2016, “When I was younger… I wasn’t scared.”

Some locations or areas can be more dangerous than others. In some places, Ritter has even been accused of being a drug dealer. “If I get there and I realize something is off, or some obvious sign that I’m not welcome, I’ll go,” she said respectfully. Ritter only wants to see the communities that more often than not go unseen, simply to see them genuinely and observe.

The insight relayed by Ritter through her artist talk about her artistic process and her own life experience expanded beyond the stereotypes and stigma surrounding these MHPs. Like all other communities, MHPs have their own stories to tell. Even if Amy Ritter does not get to know the specifics of every story, her photography and artwork is still able to capture the aura and feeling of what the house has physically lived and aged through.

Feature Image: Courtesy of Amy Ritter and the Julio Fine Arts Gallery.