On Feb. 6, students were invited to attend a panel discussion entitled “Whose Art is it Anyway?” in the 4th Floor Programming Room. This panel focused on the role public art plays in the collective memory of communities. The four panel members consisted of Nether, a Baltimore-based mural artist and activist, Jackson Forlini, a historical preservationist, Diana Boros, a St. Mary’s College Political Science professor, and Eric Moed, a public art designer and architect. Each member of the panel spoke approximately 15 minutes, detailing their experience with how public art affects the collective memory of history.

Forlini, who works at the Baltimore War Memorial, detailed his talk around the topic of “Adaptive Reuse of Monuments and Memorials.” Forlini’s main focus was on why certain immutable memorials do not make a lasting impact on society.

Forlini believes that for monuments to survive, they must make a lasting symbolic meaning. In public art, he believes that we can modify this meaning and make it meaningful for contemporary issues. For monuments to survive, they also need ambiguity. This means that the art leaves it up to the viewer to interpret, evoking a self-regenerative experience that is memorable. For example, at the Baltimore War Memorial, they have a visual art piece that evokes the horrors of the atom bomb from the Hiroshima bomb drop.

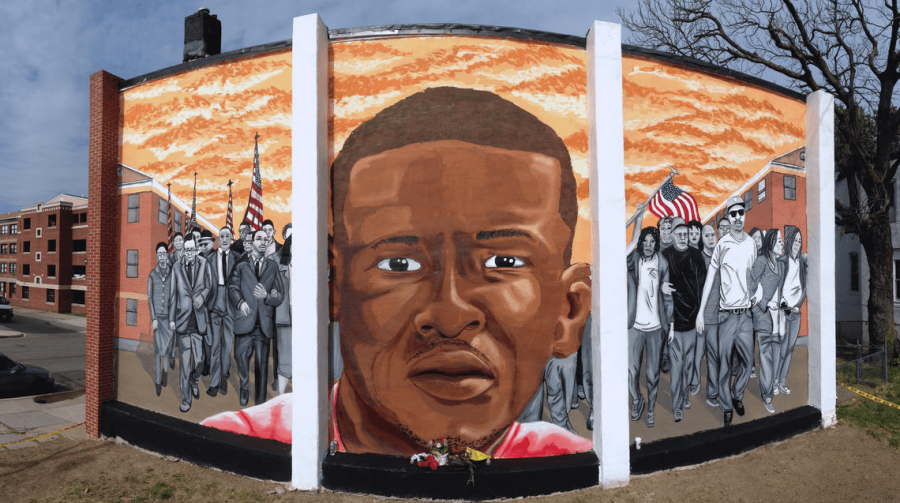

Nether spoke next, focusing on his projects in street art that directly shine a light on how art can evoke this self-regenerative experience. He detailed his work in political street art. Nether believes public art should be about the stories we need to talk about, creating a forum where we can discuss things we cannot otherwise.

One of Nethers’ pieces is about Kevin Morre, the man who took the video of Freddy Gray’s targeted arrest. In his piece, Nether included a QR code that is linked to videos and more information about the Gray incident. This inclusion of technology allows one directly to see the police brutality.

Boros focused on public displays of art in Rome and Post Soviet Hungary. The professor focused on how art displays reflected the government’s wishes. For example, in Hungary, there were numerous statues of leaders like Stalin to constantly remind the public that they were in authoritarian control.

These statues were taken down. Protestors used rope to pull down a statue of Stalin, setting the precedent for reclaiming Hungarian national power and culture. However, the reclamation of this power by local collective art has been recently threatened. The president in Hungary, János Áder, is rewriting history through public art, a history that overlooks the role the right-wing played in the Hungary Uprising.

Moed spoke last, detailing his talk around the topic of “Situated Memory, in Practice.” This architect believes that public art and memorials are containers for narratives. In his one project called “Changing Perspective,” Moed designed a bike rack display to bring light to black history in Florida. Moed’s talk further emphasized the vital role public art has in influencing public memory of the past, present, and future.

Feature Image: One of Nether’s murals in Baltimore, courtesy of BMoreArt.

Anonymous • Feb 17, 2020 at 5:13 pm

5