On Monday, Feb. 5, artist Jesse Krimes spoke about the “Creative Expression as Resistance,” which focused on his artwork and the personal experiences that inspired his work.

Krimes holds a bachelor’s degree in Studio Art from Millersville University and appears to be just like any other millennial. He took the podium neatly dressed, with gelled back hair, and addressed the assembly in a mild manner.

But what sets him apart from any other millennial? Krimes is a convicted felon.

After graduating from Millersville University in 2008, Krimes was indicted for possession of 140 grams of cocaine. Before his conviction, Krimes was held in solitary confinement in a violent offender unit in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. During his time in solitary confinement, Krimes continued creating art.

“Artwork served for me as a form of resistance, but also a kind of way to maintain a positive sense of self [while] going through these horrific conditions,” Krimes said.

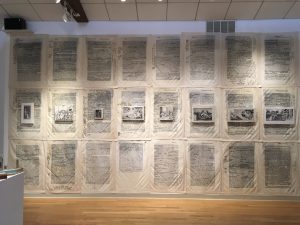

While in solitary confinement, Krimes had access to very little stimuli. However, he did have access to newspapers. Using mug shots he found in the paper, Krimes worked on a project he called “Purgatory,” a series of mugshots cut out from newspapers and applied onto bars of prison-issued soap.

“I began to notice all these very simplified depictions of people who were getting arrested. Their mugshot would be in there, and there would be some kind of narrative describing what they did. And I thought, ‘This is how they’re describing this individual: at one point in time, based off of one action,’” Krimes said. “It really forms those social norms and that stigmatization that allows you to discredit human beings as human beings that are worthy of dignity or respect.”

“Purgatory” was Krimes’ response to the simplified narrative present in the paper, a way to re-contextualize and destabilize the traditional narratives regarding criminal offenders.

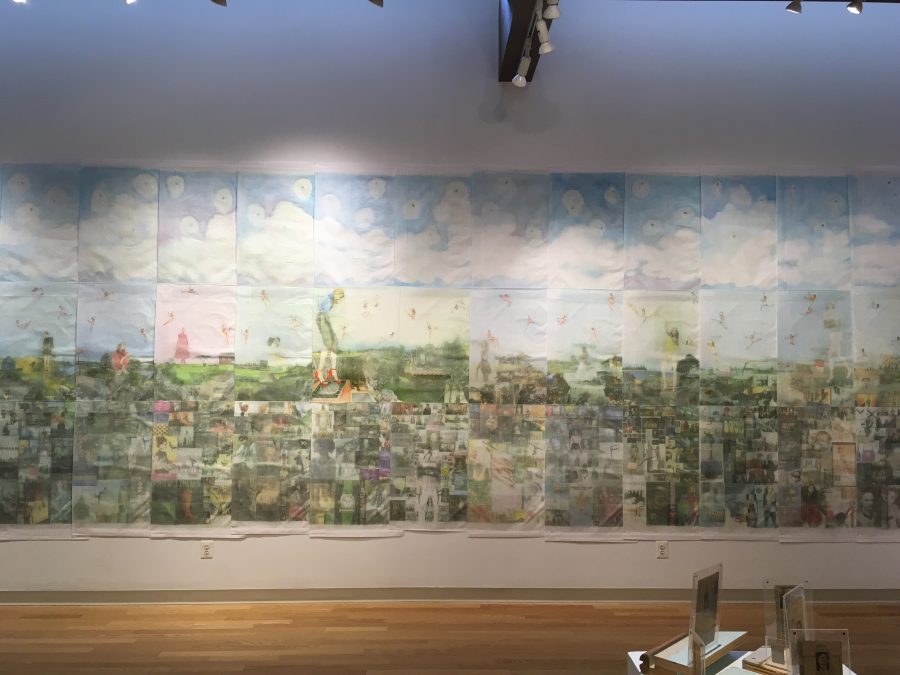

Krimes continued making art after he was sentenced to 70 months in a maximum security federal prison. He titled this work “Apokaluptein: 16389067.”

“The number is my Bureau of Prisons institution number, and the name Apokaluptein comes from the word apocalypse,” Krimes said. “Its origin ‘apokaluptein’ means to uncover or reveal, and its contemporary definition means destruction on a grand level, and so I connected the two translations of this word.”

Like “Purgatory,” “Apokaluptein: 16389067” is made using the materials that were available in prison. Materials, including newspaper images, that were transferred onto prison-issued sheets using hair gel and plastic spoons.

“I would [flip] through The New York Times and began to notice paradoxes that stood out in its imagery,” said Krimes.

However, it is not only the image transfers from newspapers that were significant to Krimes. The sheets which he transferred the images onto were significant. The sheets were produced in prison by inmates through a corporation called UNICOR.

UNICOR, also known as Federal Prison Industries (FPI), is a program that was created in 1934. According to the FPI website its goal is “to protect society and reduce crime by preparing inmates for successful reentry through job training.” FPI produces various products ranging from prison uniforms to award plaques, and also provides services such as Data Services and Call Center Services. FPI sells these goods on the private market. Inmates are paid between 23 cents and $1.15 per hour, and 5 percent of FPI’s profits are given back to the inmates that produce those goods.

According to Krimes, if we consider the fact that there are 2.3 million people in prison, which creates intense racial dynamics, that FPI makes over $800 billion, and that only 5 percent of that profit is given back to those making the goods, then we will come to the same conclusion we have.

“I mean we have the biggest plantations and slave markets going on in our country today,” said Krimes. “I wanted to use these [prison-produced] sheets to speak about this.”

Krimes left prison after five years. In 2017, Krimes received a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Fellowship, an Independence Foundation Fellowship, and a Writing Return USA Fellowship, and he was a recipient of the Open Philanthropy grant. However, he has not forgotten his experience in incarceration.

Since his release, Krimes has made and worked in collaboration with artists to create many pieces regarding the United States prison system. Pieces such as “Voices,” which was made in collaboration with male convicts who were sentenced to life imprisonment as juveniles, and the “Living Legacy Monument,” which is intended to document the historical harm of New York City’s Rikers Island prison, were all made to display the harms of imprisonment.

“We’re going to think of solutions of how to reimagine a justice system that treats everyone with fairness and dignity,” Krimes said.

For Krimes, art is the key to that reimagination.