“Why is it so hard to stand up for black folk? Why is it so courageous? Why is there so much risk involved in speaking out against injustice?”

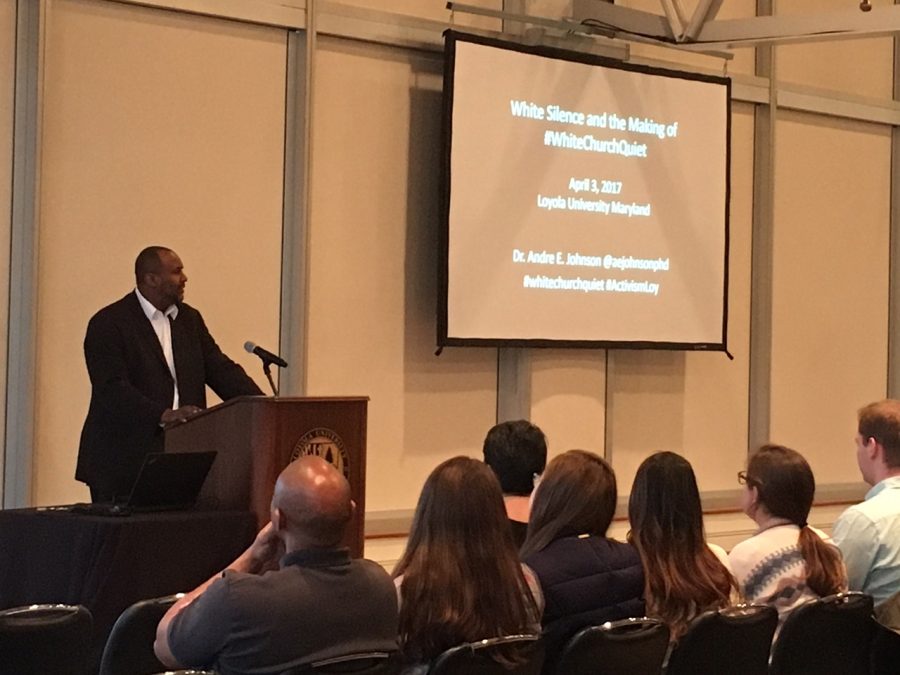

These are the questions that the Rev. Dr. Andre E. Johnson asked Loyola on April 3 at the lecture “White Silence and The Making of #WhiteChurchQuiet.” Johnson founded the hashtag in 2016 in response to the white Church’s silence on police brutality.

The talk, sponsored by Messina and CCSJ, called audience members to have empathy for and awareness about these issues.

“We should all care when innocent people are being targeted, when innocent people are being killed,” Jean Lee Cole, Ph.D., said in her introduction to the talk. Cole is the inaugural faculty director of community-engaged learning and scholarship and helped bring Johnson to campus.

Johnson helped to frame this cry for empathy in light of race relations in the United States and in relationship to the Christian Church. As he has observed, if there is any type of Christian response in the aftermath in one of these events, it is from the black Church.

“The story of Jesus is someone being set up by the State. They thought they were getting rid of a bad dude. His death was nothing special: they had two other guys [there] at the same time,” Johnson said. “This is relatable to the black community and the black struggle. It’s one of the reasons why we have the tradition of social justice, of liberation [in] the black Church.”

But where is the white Church? Why aren’t white Church leaders speaking out?

Johnson cited recent research that states that while over 80 percent of black Christians believe that police brutality is part of the picture of race, about the same number of white Christians believe the opposite, that police killings are isolated incidents.

“If you already come to the table not believing my truth, how can we really get things accomplished?” Johnson said.

Johnson often referred to Robin DiAngelo’s idea of white fragility as an explanation for the Church’s silence. White fragility is the idea that “even a minimal amount of racial stress becomes intolerable,” he said.

White fragility is responsible for the cry of “All Lives Matter!” in response to “Black Lives Matter.” This reaction often “tells me something about who you think black people are,” Johnson said.

Johnson also referred to the Department of Justice’s report on the Baltimore Police Department after the death of Freddie Grey. The testimonies and stories offered in the report are ones that are “shared by countless African Americans across the country,” he said.

To Johnson, the report is also a sign that there is a problem.

“Does the white Church believe black truth? Do you see me as human?” Johnson said. “How many times do you have to hear the same stories over and over and over and over and over and over again before it beings to resonate as true?”

And yet, Johnson understands white Church leaders’ silence: speaking out means risking one’s job and career, friends, and family.

“To admit [police brutality is part of the picture of race in America] damages their idea of America, it causes them to reexamine what they think of black people in the first place,” he said.

Johnson may understand the roots of the silence, but by no means does he justify it. “To have the evidence right in front of us and to still not [be] empathetic is problematic,” he said. “And that’s the nice way to put it.”

Johnson ended his discussion by reviewing Loyola’s Mission Statement. The statement makes it clear that all human beings are made in the image of God and that everyone is a child of God.

“If that’s true, then if I’m seeing black bodies laying on the ground, I can be empathetic [because] that’s my brother or my sister laying dead on the street,” he said. “That’s all we need.”

To catch up on the discussion, view #WhiteChurchQuiet and #ActivismLoy, where students livetweeted the lecture as well as some of the class discussions in which Johnson participated.