“Baltimore, you’re listening to W.E.E.D. 95FM, ‘The Psychadelic Pig.’ Today’s colors are sounds… you hear ‘em? It’s the sounds of silence. And it’s golden. And you’re here today to share that moment in time. You will remember this… If we allow you to, if we allow you to, if we allow you to, if we allow you to…”

Former Baltimore radio host, photographer, and creator extraordinaire Bobby Adams sat on his bench across from me and reenacted clips of his old radio show, holding his hand up to his ear as we listened for colors. The sun was shining, the water of Middle River was sparkling, and the silence truly did sound golden. But we quickly broke it – Bobby had a lot to say.

I initially called him after falling in love with his work that was featured in the Big Hope Show at the American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM). The yearlong exhibit closed Labor Day Weekend, but Bobby has new art on display in AVAM’s “YUMMM!” Exhibition, which just opened last month. When I first called for an interview, he sounded disheveled and short. “Come over tomorrow. I can give you an hour,” he said.

I initially called him after falling in love with his work that was featured in the Big Hope Show at the American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM). The yearlong exhibit closed Labor Day Weekend, but Bobby has new art on display in AVAM’s “YUMMM!” Exhibition, which just opened last month. When I first called for an interview, he sounded disheveled and short. “Come over tomorrow. I can give you an hour,” he said.

But Bobby ended up telling stories for much of the afternoon.

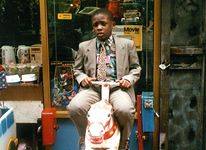

At 70 years old, he now sells antiques and lives with his new dog, Mya. Forty years ago, he was living in Baltimore County on 200 acres of land in the oldest house in the area. This was his life when John Waters – infamous director of “Pink Flamingos” and “Hairspray” – found him and asked to film a movie on the property.

“I said, ‘Absolutely,’ cause, you know, we were young, crazy kids making little, funny movies, and the name of the movie was ‘Pink Flamingos.’” So the John Waters crew put a trailer in the back and borrowed around $10,000 to film. “Nobody got paid and everybody worked hard to do it… before you know it, it was shown in New York at the Elgin Cinema.”

In addition to becoming a part of Waters’ most popular films, Adams also found his photographic beginnings without realizing it. He was simply enjoying himself and snapping photos while Waters and Divine, Baltimorean drag star, put on a show.

From that point on, Adams was a member of Waters’ “Dreamlanders,” the crew of characters who repeatedly worked on his films. He was always there to capture shots behind the scenes, and once even stepped in front of the camera himself for a brief cameo as Ernie in Waters’ film “Female Trouble.”

Years later, as Adams and Waters were getting older and the days of “making little funny movies” together had slipped away, a woman named Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, founder and curator of AVAM, cast a new light on the thousands of photos Adams had taken during that time.

Hoffberger and Adams had met at one of Waters’ Christmas parties, but she hadn’t known about his photography at the time. One day, while rearranging her office, she found a postcard of two redheaded boys giving the finger and flipped it over to find Waters’ name on the back.

“And she calls me up and says, ‘I didn’t realize you did this… I have to come out and see everything you ever did,’” he said.

To see everything Adams has ever done is quite a feat. His office is stocked with memorabilia from a radio show he hosted in the ‘60s and countless messy piles of photos he shot during Waters’ movies. The photos are filled with people who the world considered “weird,” but through his lens, Bobby shows the beauty in their imperfections.

Later on in his career came “Odie Art.” The project is a collection of over 100 pieces of art dedicated to Bobby’s dog, Odie. When Bobby was a DJ back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, he spent hours making scrapbooks for his listeners to pass around. Later on, he made them for people he loved.

Later on in his career came “Odie Art.” The project is a collection of over 100 pieces of art dedicated to Bobby’s dog, Odie. When Bobby was a DJ back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, he spent hours making scrapbooks for his listeners to pass around. Later on, he made them for people he loved.

Bobby even makes art out of Christmas cards. Every year, he makes cards for over 200 people. If you’re in his address book, you’ll get a card, no matter how long it’s been since you’ve seen him. Bobby is the kind of guy who touches your life forever. Once you’ve entered his world, he’ll never forget you.

When I called Rebecca to talk about Bobby, she said the thing she admires most about his work is “the way he makes an art out of friendship.” For the first time in the history of her museum, she gave him his own room in an exhibition as a new artist.

Bobby was shocked. He didn’t consider himself an artist. When I asked how he sees himself, he laughed and said “somebody that cuts out paper dolls.”

In her first phone call, Rebecca promised him that he is everything a “visionary” is. When he called her three days later saying he could not do this, she simply said, “Bobby, I would never have chosen you to do this if I didn’t think you could do this. If I didn’t know it was in you to complete this, I never would have told you otherwise.” Then she hung up.

“I was not happy with her at that moment, tell you the truth,” Bobby said.

But then he read the definition of visionary art: “art produced by self-taught individuals…whose works arise from an innate personal vision that revels foremost in the creative act itself.”

He realized she was right all along.

Bobby became the leading artist in AVAM’s The Big Hope Show, an exhibition that displays the power of hope through art. Each featured artist has created work deepened by tragedy, but inspired by the hope of new beginnings.

Bobby has a tumultuous past. His mother committed suicide, he struggled with school and being labeled “different.” He later had to deal with the death of his beloved dog, along with an overeating problem.

Through art, and more importantly, through the love and friendship that inspired that art, Bobby has maintained a positive outlook on life. But what was most amazing about Bobby’s art in The Big Hope Show is not the hope it has given him, but the hope it gave everyone who saw his exhibit. Throughout the show, Bobby spent a lot of time chatting with people who passed through.

Through art, and more importantly, through the love and friendship that inspired that art, Bobby has maintained a positive outlook on life. But what was most amazing about Bobby’s art in The Big Hope Show is not the hope it has given him, but the hope it gave everyone who saw his exhibit. Throughout the show, Bobby spent a lot of time chatting with people who passed through.

“You know, sometimes I [wouldn’t] feel like going in,” he said. “But I tell myself, ‘you never know who’s gonna need to hear that story today.’”

He told me about one visitor who was so moved by Bobby’s work that he introduced Bobby to his entire family. He even shared his own story of suicide attempt. Another visitor has come down from Philadelphia over and over again just to sit in Bobby’s exhibit. She said everybody in that room has loved each other and she could feel that love.

“We cannot make a success of our life without making a gift of it, and when we give ourselves away to other people, like I’m talking to you, when you make a card, when you make a scrapbook, you’re touching somebody else’s life,” Bobby said. “That is what’s important.”

Bobby has new art on display at AVAM and he hopes to move on to other creative projects as well. The Big Hope Show may have ended, but his sharing will go on.

“When you get into your 70s, that’s a time when you can slow down and create more again,” he said. “Now that I’m in my senior time… I can share what I’ve learned and what I’ve learned is to love freely and without anticipating anything from anybody else. To learn to love myself. That’s the hardest to learn. Once you realize that cup that you’re drinking from is important to you, then you can share that cup with everybody else.”

Before I left his home on that sunny Maryland afternoon, Bobby put on his radio voice for one last reenactment: “Baltimore, whatever goes up must come down! Baltimore, you be careful! When you go up tonight, you’ll be going down tomorrow!”

Feature Image: Washington Post Photo

All In-Text Photos Courtesy of Mackenzie Lowry