Prospective journalists everywhere were saddened last week to hear the news that Condé Nast has shut down its popular internship program.

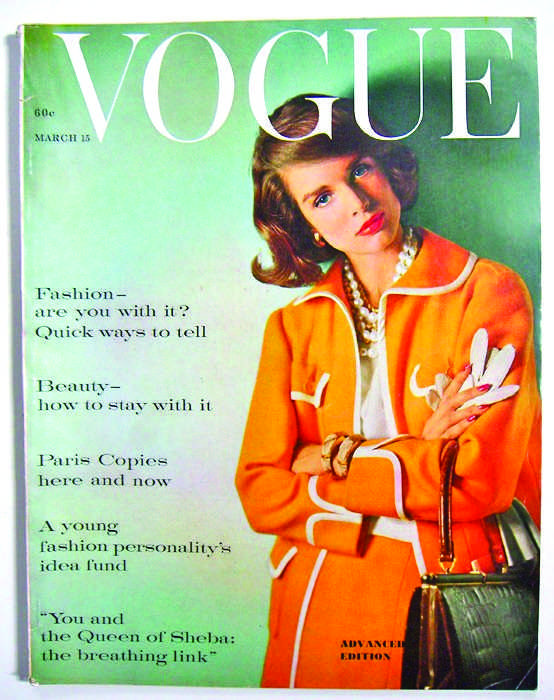

Condé Nast owns over a dozen well-known magazines, such as Vogue, Teen Vogue, Glamour, Wired, Bon Appetit, Details, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, W and others. Previously, these publications offered much-coveted internship positions for college-age students.

However, following a recent lawsuit filed against Condé Nast, the company decided to terminate its internship program starting in 2014.

The Condé Nast lawsuit follows an important court decision resulting from a similar case this past June. Unpaid interns working for Fox Searchlight Pictures filed a suit against the film company after working on productions such as the 2010’s Black Swan, claiming they were overworked and inappropriately uncompensated. The presiding judge decided that the interns were “misclassified” as such, and because Fox reaped the same benefits and from the work of these interns as they would have from paid employees, that the company violated minimum wage laws.

Interns at various Condé Nast magazines followed suit—that is, filed a suit—against the magazine conglomerate. Although these interns were paid, the pay (more like a stipend than an actual salary) apparently yielded less than a dollar per hour. That’s more than six dollars less than New York City’s lawful minimum wage. With that in mind, the interns essentially likened the strenuous amounts of work (up to a reported 55 hours per week) to glorified slave labor.

Although this case is still ongoing, Condé Nast preemptively decided to terminate its entire internship program. Many think that Condé Nast’s position on the issue is extreme, and that shutting down the program entirely—instead of making alterations—is a bit ridiculous.

However, the only possible change to be implemented that could have presumably avoided these lawsuits would be to pay interns minimum wage. Then the question arises: What is the difference between an internship and regular employment?

Some have offered that since interns are generally pre-entry level and currently seeking degrees, the ability to receive college credit for the position is fine in place of minimum wage pay. Many still think the suits are ridiculous, and that internships offer invaluable experience in a competitive industry—and that’s pay enough.

Junior Hanna Zirinsky sounds off on the issue, “You’re not always going to get paid at an internship. For instance, I’m at an internship now that’s unpaid. The fact that these interns were making at least some money is better than nothing, if you think about it. If you want to be paid minimum wage or more, then don’t apply for internships that don’t offer that—apply for jobs.”

“Money obviously plays a factor,” adds Juliana Marothy, also a junior. “But the experience you get from immersing yourself in a company and a field that you’re passionate about is priceless. Yeah, receiving a generous stipend or more than minimum wage would be nice, but not every company can offer that, although they can offer you insight into what they do and how their industry works. It’s a matter of deciding which is more important for you. If experience is going to matter more in the long run, then the pay shouldn’t be the biggest factor when it comes to internships.”

Although it seems like most students understand they will likely have to sacrifice standard pay when it comes to intern positions, it is unlikely that Condé Nast will reinstate their program any time soon. This decision has created a rippling effect of negative consequences, hurting not only potential interns but also the magazines themselves. There are several questions to consider: Who will now perform the tasks once relegated to interns? Moreover, if other companies follow in Condé Nast’s footsteps and eliminate unpaid or low-wage internship programs to avoid litigation, how will young people obtain the experience needed to pursue their desired career?

As mentioned earlier, these Condé Nast internships were an excellent way to introduce hopeful journalists into the industry, providing them with a wealth of experience and—perhaps more importantly—networking opportunities. Now those opportunities will have to be found elsewhere. I personally have been planning to apply for an internship with Condé Nast the summer after my junior year—meaning this upcoming summer—since before I began college. These plans, though, have had to be completely scrapped.

Besides those simply looking for summer internships, several undergraduate and graduate programs require internship experience of their students. These schools and their students have now lost an important resource. For instance, the magazine writing journalism graduate program at NYU requires that its students complete at least one internship throughout the course of the three-semester program. On their site, they list previous internship placements of students in the program; a large chunk of the publications listed fall under the Condé Nast umbrella.

Enrolling in this program (and others like it) used to mean a guaranteed journalism internship. However, with a large portion of relevant magazine internships now unavailable, this may no longer be the case. Not only are these important publications off the table when it comes to interning, but competition at non-Condé Nast magazines will increase sharply—and perhaps a position anywhere will no longer be guaranteed at all.

As a writing major and prospective journalist myself, I was interested in the NYU magazine writing program in particular specifically because they were so well connected to the Condé Nast magazines, where I would ideally like to pursue a career. After this decision, though, I may have to reevaluate my intentions for the future and whether this program makes sense for me. Many other students of writing or journalism are, I’m sure, in a similar position.

Although it’s understandable why the decision was made at Condé Nast, it is disheartening for those who were hoping to get the chance to intern at one of their publications. There will always be a large supply of young people interested in working at these magazines, and while pay would be nice, most would do it simply for the chance to build skills and contacts in a very narrow industry (myself included).

With any luck, Condé Nast will realize this and bring back their program, perhaps reformed, in the coming years. While it will likely be too late for me if or when this happens, there will be a new wave of eager writers ready to fill the positions.

Until then, the rest of us will have to look elsewhere for ways to occupy ourselves during summer break.