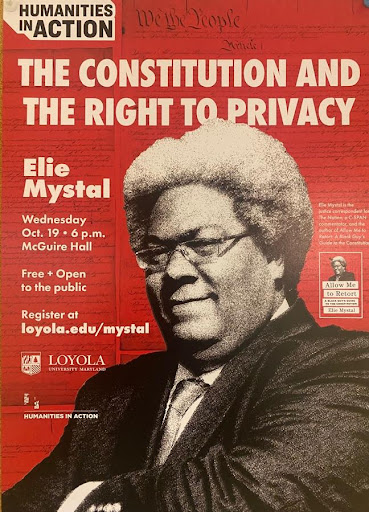

McGuire Hall was standing-room only to hear Elie Mystal speak about what he views as increasing government infringement on personal liberties. Spurred by the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, Mystal’s speech centered on the concept of the right to privacy and some now-vulnerable rights.

The right to privacy, established in the 1965 Supreme Court ruling in Griswold v. Connecticut, has set precedent for the legal protections of abortion, marriage equality, adoption equality, access to contraceptives, and a general right to the private sphere. Originally protecting married couples’ right to birth control, this long-standing precedent of privacy has extended critical protections to many Americans.

After restricting women’s reproductive rights in Dobbs v. Jackson this summer, Justice Clarence Thomas announced what many in the United States feared; the Supreme Court will review its protections stemming from Griswold.

Mystal said, “When people attack the right to privacy in the context of abortion, they are not attacking abortion. They are attacking the entire thing.”

The right to privacy can be rolled back so significantly because, unlike protections such as the right to freedom of speech or freedom of the press, it is not enumerated in the constitution. Instead, Mystal claims, its absence from the constitution is due to its structural function within the document. He says that for all other rights to exist in the constitution, there must be an implied right to privacy. If there were no such right, there would be no need to outline citizen-state relations.

Mystal compared the right to privacy to a black hole. Both, although invisible, are components of systems that would not make sense without their existence.

“There’s nothing visual we can have to know a black hole exists. The way we know a black hole exists is that we can’t explain the rest of the orbital bodies moving around it without it existing. Something has to be there,” said Mystal.

Students and staff seemed to enjoy Mystal’s ability to critique such pressing issues with biting, witty sarcasm. His speech elicited groans of affirmation and chuckles after anecdotes—including a comparison of due process to his kids’ time on Minecraft. Questions after the speech primarily focused on what the future of rights looks like in the United States. Students came to the podium to know how their lives are going to be affected in the upcoming years. In particular, students wanted to know what elected leaders in the government can and may do in their push for and against the right to privacy.

“I wasn’t expecting him to say as much as he did. I really liked his point about how it’s not the kind of people they are, it’s about where they want to end up and what they’re willing to do for it,” said Mari Fofana ’26.

Highly critical of the current state of the Supreme Court, Mystal remained optimistic that the right to privacy could be protected through actions like packing the court or doing away with judicial review. He maintains that the Supreme Court has a long history of anti-democratic rulings which have led to systemic inequalities. He wants a democracy, not a juristocracy.

Highly animated, Mystal spoke to the protection of rights for all people. He says that the right to privacy is critical in the attainment of this goal.

“Every person should be treated like a person,” Mystal said. “People should have people rights, and people who don’t think people should have people rights—are wrong.”

Featured Image courtesy of Jeremy Ahearn.