James Blake was never going to win ‘Best New Artist.’ Stacked up against the Grammy-nabbing Macklemore, Kendrick Lamar (who left the ceremony criminally award-less), Ed Sheeran and Kacey Musgraves, Blake, a 25-year-old British crooner/electronic producer, didn’t stand a chance. It wasn’t just unfair—it was cruel.

That’s not to say Blake didn’t deserve to be up there—he won the 2013 Mercury Prize (Britain’s Grammy equivalent) for album of the year, beating out favorites David Bowie, the Arctic Monkeys and Disclosure for the honor. His various albums and EPs have run the gamut from electronic soul to London dubstep (vastly different than its American cousin—more on this later), creating a sound all his own.

So, who is he?

James Blake Litherland, born in London, is the son of British guitarist James Litherland. Following in his father’s footsteps, he was classically trained as a pianist and went on to receive a degree in popular music from Goldsmiths University. His first 12” release was entitled “Air and Lack Thereof,” featuring distorted, looped vocals, dark ambience and an off-kilter chattering beat.

These sounds came to define South London underground dubstep, which paired with his nuanced mastery, made Blake a favorite of the scene (Blake is famously critical of American dubstep, describing the “frat boy attitude” and the race to see who could make “the dirtiest, filthiest bass sound” as “millions of miles from the ethos of [the genre]” and a “pissing contest”).

The strength of his releases grew exponentially, leading up to the CYMK EP, a heavy, boundary-pushing effort that received ravenous praise from indie tastemakers Pitchfork.com. Still, he didn’t break through to widespread radio play until he released his cover of “Limit to Your Love,” a song off Feist’s album The Reminder. It was one of his first releases with Blake’s rich, soulful voice on full display. On the track, he croons over bare piano and minimalist drum breaks, occasionally layering his voice with studio trickery and souring it ever so slightly with digital effects.

“Limit to Your Love” received radio airplay, though it became more than James Blake’s first hit. It was uncharted territory—a crossover hit melding heartfelt soul and icy electronics. There were few, if any, artists that sounded like this—his progressive dance music morphed into something daringly new. James Blake became peerless.

His debut album, simply titled James Blake, continued in the vein of “Limit To Your Love,” further establishing his patented “James Blake sound.” Tracks like “The Wilhelm Scream,” a cover of one of his father’s songs, “Where to Turn,” takes a few lines from the original, and layers distortion and aqueous percussion hits over its simple, lilting melody until its otherworldly climax. “Measurements” finds Blake looping his voice a capella a dozen times at different intervals and octaves, creating the effect of a gospel choir from his fragile voice alone. “Unluck” features a clicking beat with interspersed 8-bit effects; his voice warped beyond recognition, becoming another instrument in the mix rather than the centerpiece of the song.

Blake continued to toy with this formula on his newest album, Overgrown, to great success—his voice has become less processed (likely due to the confidence-boosting reviews of his self-titled debut) and the pop arrangements have become even tighter. The melancholy title track features bounding sub-bass, backing Blake’s tender crooning as he sings, “I don’t want to be a star, but a stone on the shore.” “Retrograde,” possibly Blake’s most successful single of his career so far, is a tour de force of excellent songwriting. The song begins with JB humming the melody over a barebones electronic beat, which sizzles with vintage synthesizer and Blake’s hair-raisingly powerful vocal delivery. “Life Round Here” features a circuital piano line with a snapping beat that lends itself well to hip-hop (a song which was recently remixed by Blake and up-and-comer Chance the Rapper).

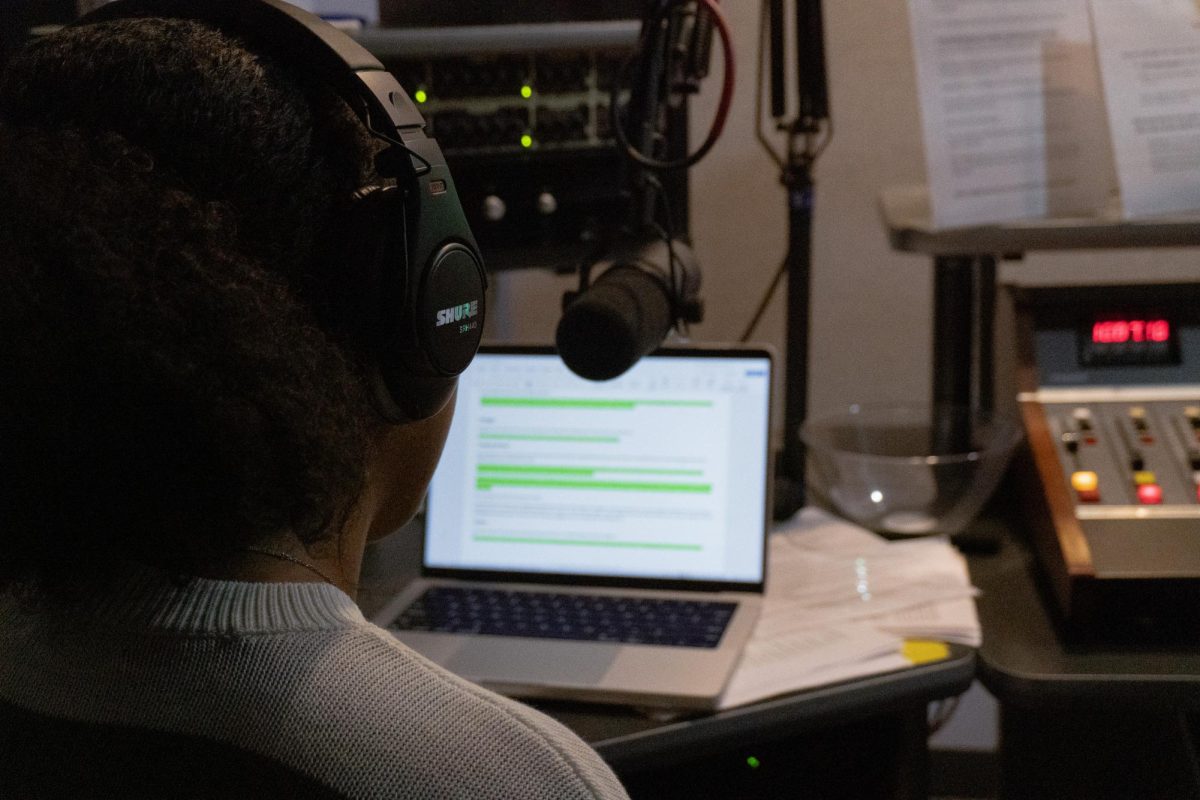

I’ve had the good fortune to see James Blake live. He plays piano and synthesizer and has a guitarist and a drummer with him onstage. That’s it—nothing is pre-recorded and everything is done live, right before your eyes. Each song took on a new life in the live setting with extended codas, sampling and infectious dance breaks. I’ve seen dozens of concerts in my life, yet nothing quite like this—it was revelatory.

I’m not going to sit here and pretend that James Blake would ever take home ‘Best New Artist;’ though it’s a shame that a young artist of such limitless talent wouldn’t stand a chance. Blake, much like other musicians ahead of their time, will have his legacy and music cherished long after “Thrift Shop” (or any of-the-moment pop for that matter) is off the radio rotation. That in itself is a reward.