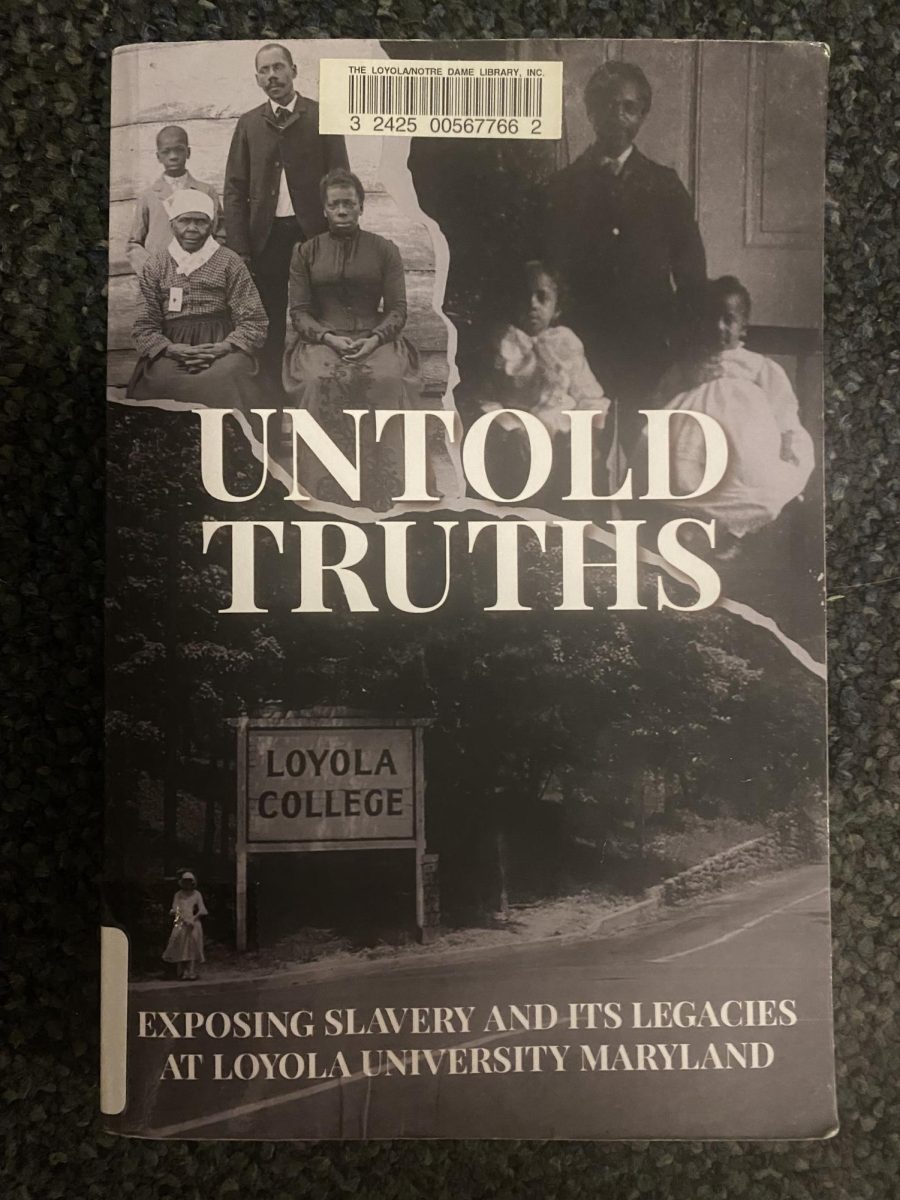

During my summer research on Baltimore’s African American burial grounds, I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. David Carey from the history department on his work in the “President’s Task Force Examining Loyola’s Connection to Slavery” project. From this report, students and faculty published their findings in an anthology titled Untold Truths: Exposing Slavery and Its Legacies at Loyola. The following is an interview about his and other participants’ research experiences and on ongoing dialogue on Loyola’s campus.

Thompson: How did you get involved in the Task Force and what was your research approach?

Carey: I did [a book club] on Ebony and Ivy that was a book about the way in which the ivy league schools and most northeastern schools benefitted from the slave trade and actually had enslaved peoples working on campus. That got me thinking we should try to figure out what our own history is. With a colleague, Lisa Zimerelli in English and Jenny Kineff in the library, we submitted a grant to the Center for Humanities, an Aperio grant that allows you to give students research stipends for summer research and then teach a course based on the research and publish their papers with Apprentice House Publishing at Loyola. At the same time, we were applying for that grant, it was unbeknownst to us at the time, but the university, the provost and the president, were also forming a commission to look into this. That’s what drew me into the project; it was a nice little confluence of events. The thing that’s remarkable to me about the project more broadly is it’s mostly undergraduate research that’s informed these histories that we’re aware of. There were some that did oral histories with descendants of enslaved peoples that were sold by Jesuits, so it’s really been a student-driven project which I think makes Loyola’s experience distinctive in really rich ways. As you can imagine, it’s difficult stuff to find out about your own institution, particularly for Black students, the way that they were perceived and treated at Loyola. There’s some wonderful essays about that whole process in Untold Truths.

T: What was the process for finding primary sources (given struggles with lack of documents and mostly white perspectives in the archives)?

C: One of the major challenges we faced was trying to understand who were these people? It was hard to even get names of people who had been enslaved, specifically tied to Loyola. We know the names of the 272. Loyola actually hired enslaved peoples. One of the first presidents of Loyola contracted to have enslaved peoples working here, but we don’t know those names. So many of the Black free laborers thereafter, we still don’t know the names. We worked with the Afro-American, the Baltimore Sun, we went to the archives at Georgetown University because they hold the Jesuit archives. We worked a lot in Loyola’s archive. We worked at the Center for Maryland History and Culture and the Enoch Pratt Library, and we did a little bit of research at St. Ignatius which is a Jesuit Parish in Baltimore that was actually connected to Loyola when it was first founded in 1852. So it was really a broad net that was cast, and it was really thanks to Jenny Kineff, the archivist that helped us figure out where we should be looking, what we should look for.

Getting back to the challenges, how do you write this history in a way that isn’t only written from the perspective of white male scribes and reporters and journalists? Ikia Robinson did this fantastic essay on Charles Dorsey who was the first full time Black student in 1949 at Loyola. She paints a really full and rich picture of who he was. It’s hard to know what his experiences were at Loyola. We can know different things that happened in terms of there being blackface on campus while he was here, issues around the junior prom–those things we know were going on at the time but not necessarily things he was thinking about.

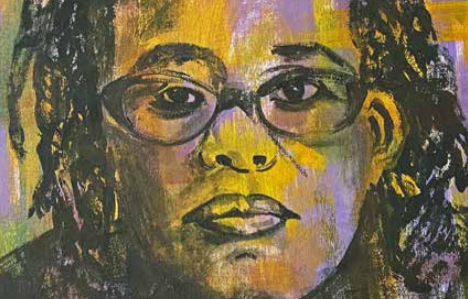

One of the things that we found at the archives at St. Ignatius was a photograph of Madison Fenwick, and he was a Black laborer in the late nineteenth early twentieth century on Loyola’s campus. He worked in the dining hall. It was such a rush to see an image of him, to actually have a face of someone we learned about.

T: Have you witnessed resistance to your research?

C: I did have this conversation with one alum who’s been a donor for years and had told me that he would oppose it absolutely if they tried to change the name [of Jenkins Hall], and I kind of explained to him that our approach and thinking through it was like is that harmful, is it hurtful for people. And we have heard from Black students and families and residents that it is actually harmful to go into a place named after someone who’s said that enslaved people are happy to be enslaved and were better off being enslaved. Within like thirty seconds he’s like okay change the name. I think there’s ways in which you can have conversations to break down that kind of resistance.

T: What do you think memorialization will look like on campus?

C: I think that’s really crucial, and actually Lynn (Nehemiah, GU272 descendent) has just made this so compelling. She talked about when she first came to Loyola with her son when he was looking at colleges, and within fifteen minutes she was like forget it, this place has no recognition of what my ancestors have done to build this. I think one of the ways that would be nice to see [memorialization] happen is on the Jenkins building. He was a confederate soldier and proponent of the Lost Cause, so recommendations about changing that name, maybe it becomes the Charles Dorsey building or something like that as a way to recognize the pasts that Loyola’s part of.

T: What was something from your research that stuck with you?

C: [In] Noah Hileman’s essay, he figured out that the green and gray of Loyola’s colors, the gray is a nod to the Confederacy. Those sorts of things. The Charles Dorsey story was pretty amazing, there’s also a woman named Mary; she was the first African American graduate student in 1952. There are ways in which so much of this history is depressing and tragic. Landon Miller was saying you got to uplift people as part of this, you got to find some joy here, so that’s the stuff that in the end percolates to the top.