The Muse is a creative publication that aims to share the interests, talents, and research of students on campus. The following represents the opinion of the student writer and does not represent the views of Loyola University Maryland, the Greyhound, or Loyola University’s Department of Communication.

This section of “The Muse” is all about the different kinds of research going on at Loyola. Whether being conducted between the library’s shelves or underneath microscopes, academic research serves as an essential component of the college experience. Professors’ work informs their course material, undergraduate research builds critical analytical skills that can help our future careers, and all the studies serve to strengthen intellectual discussion around our campus. In recognition of these programs’ importance, I’ve reached out to students and professors across campus to ask them to share a little about their experiences with research.

For this month’s article, I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Andrew Ross, an accomplished professor and writer from Loyola’s History Department. Dr. Ross has taught at Loyola for 6 years and serves as both an academic advisor and an important figure in the honors program.

What areas of research have you engaged with the most throughout your career?

I’m primarily a historian of modern France, especially in the 19th century and the history of sexuality.

So my first book was a history of homosexuality and prostitution in 19th century Paris. And I’m currently working on a project that explores the campaign to abolish moral policing in late 19th and early 20th century Paris. I also have published work on how to use archives in the history of sexuality and more generally on the history of sexuality in French history.

What initially led you to finding that area of research and your relationship with the topic of interest over time and as your careers evolved?

I came to this area of research somewhat by happenstance. I fell in love with Paris when I was in college, when I was able to visit. I had a professor when I was a freshman who was a French historian, and they became a real mentor to me. So I turned to French history and also fell in love with 19th-century French literature.

I also became a historian of sexuality as I discovered that this was an existing field through my involvement in queer social groups and activist groups on campus at Washington University. I was able to combine the two interests, though I originally wanted to be a historian of gay life more exclusively than I ended up becoming. It was through my encounters with the archives, especially police archives, that I broadened my interests to kind of, at least in my first project, public sexuality.

So I also addressed female sex work in that work. Now I’m more interested in relating the history of sexuality to histories of the police, especially around conversations about police abolition and that sort of thing.

So my work changed from kind of a more specific area of interest to something a bit more broader over time.

If you don’t mind me asking, what were some of the challenges when you first started researching and publishing your topic? Were there limitations on access to materials or primary sources?

Well, historians always face the issue of which primary sources are still going to be in existence.

One example is that many archives actually burned in 1870. So a lot of the kind of administrative materials and police archives from about 1850 to 1870 no longer exist. So that was an issue. But fortunately when you work in the 19th century, if the document exists, French public records laws basically means you can access it. If it’s in an archive, you can get it. You don’t need special permission. But I began this work in the early aughts (2000s) where the history of sexuality, especially in France, was not really that well respected.

So it was a bit of an issue telling archivists that I was interested in the history of homosexuality and whether they would be that helpful in locating materials was always kind of an open question. But gradually as the archivist kind of came to know me a bit better I was able to kind of overcome that problem.

Do you think that, generally speaking, the social climate for academic discussion around the topic of public sexuality has improved in the last 20 years?

Certainly. I mean at least in the United States and Britain, the history of sexuality is fairly mainstream at this point.

Like people don’t really question whether or not it needs to exist. That is not quite the same in France, which has always struggled to kind of accommodate histories of marginalized peoples. That’s for a variety of reasons that I’m not sure it’s worth getting into.

It’d be another interview?

Yeah, it’d be another interview, exactly. Things are getting better there too, but it always feels like they’re a little bit behind the anglophone world in terms of incorporating histories of women, peoples of color, histories of queer people into the mainstream. But certainly, I have no issues getting my work read and acknowledged here in the United States. Whether fellow historians will integrate histories of sexuality into their broader narratives of, say history of urbanization or politics, remains a challenge.

What type of student research have you overseen at Loyola?

The research I have overseen, or assigned, has all been in my courses, which can take a variety of different forms.

And what would you say are the most important things when you’re helping students develop their research or grading their final papers?

The biggest thing is the ability to make a convincing argument. I think that sometimes when students enter a history course, they’re under the impression that the goal is just to tell a story. But history is not a discipline of fact recovery, it’s an interpretive discipline. Therefore, people are going to disagree with one another; the key to a good research project is to not just tell the instructor what you think occurred, but why and how.

Then you use evidence, in a history class usually primary sources, to support your argument, which must be debatable. In other words, the strongest research projects are those with the most complex, nuanced argument that is then successfully proven through the use of evidence.

If students are struggling with writing their papers, what are some useful tips you’d recommend?

Outlining. It can be extremely helpful, especially if one thinks of a thesis statement as a kind of argument that proceeds in a certain order, right? The argument itself should lay out what the paper will do, and then an outline can start with just the topic sentences of each paragraph. These establish what each paragraph will do in relation to the argument. If you have a solid outline, you’ll be able to read all those sentences and know what this paper is doing for you and in what order.

The second thing I’d say is that the first draft is often not the one you want to be turning in. Revision is absolutely essential to the writing process; writing is not only something you learn by being taught, but by doing, and revision is a part of that process. You have to be willing to redo what you initially put on the page.

With some of the papers and books that you’ve published, how many drafts have you gone through?

Um, uncountable. *laughs*

For students looking to undertake research in the humanities, are there any specific programs or opportunities you recommend for students to pursue?

The most important place to go is the Center for Humanities. I will not try to list all of their opportunities, but they include internships, independent research projects, digital humanities, summer institutions, all types of opportunities.

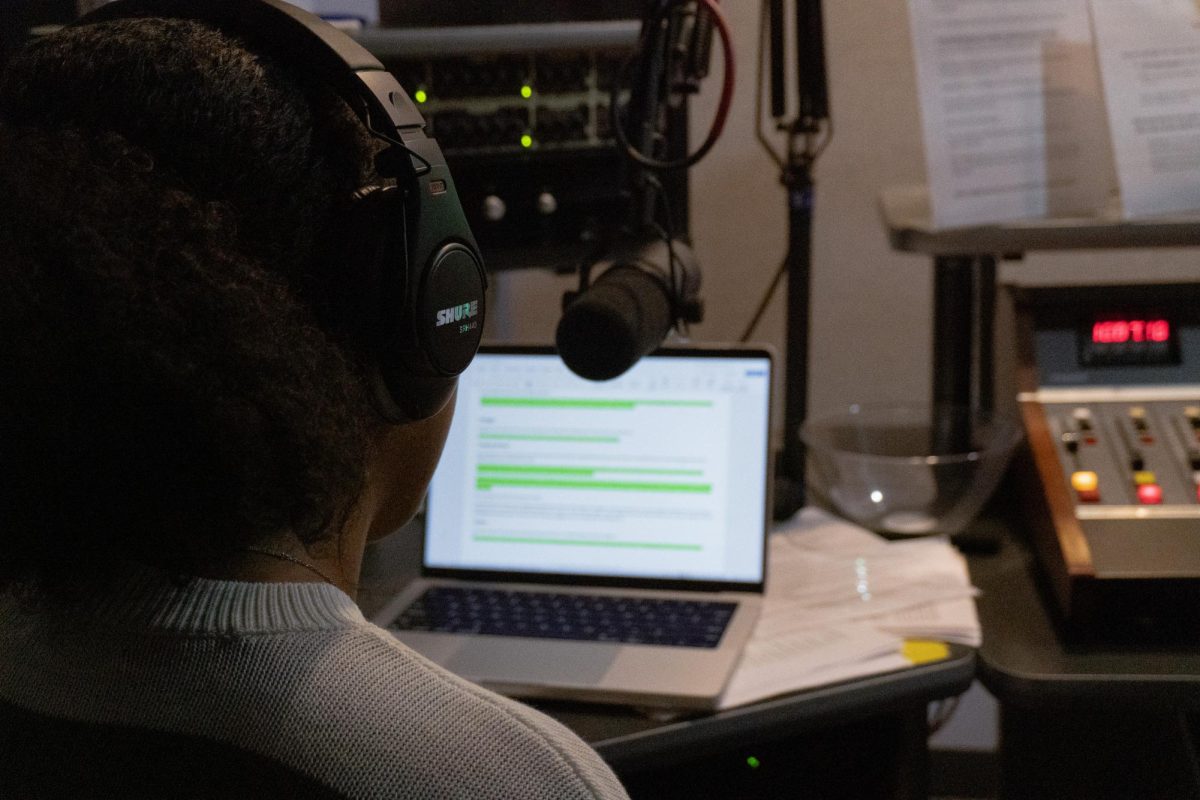

In any upper-level history class, there’s a research component as well. It won’t always be a paper; for example, in my class Sex and the City (HS 328/416) the final project is a poster presentation. In other classes, it might be a website or other different formats as well. In my study abroad course, we’ve done podcasts, which is a booming arena for public history.

What are your thoughts on the usage of these different formats for discussing research?

It’s important to understand the use of analytical essays. The ability to think through the relationship between evidence and argument in the written form is critical, but there’s different ways you’ll be making arguments in your life, and a lot of those will be oral. So just thinking about the different kinds of communication we use is important, and I encourage people to consider them.

Thank you again to Dr. Ross for agreeing to the interview; his office is HU 311, on the 3rd floor of Humanities. Please stay tuned for the next interview on The Experiment!