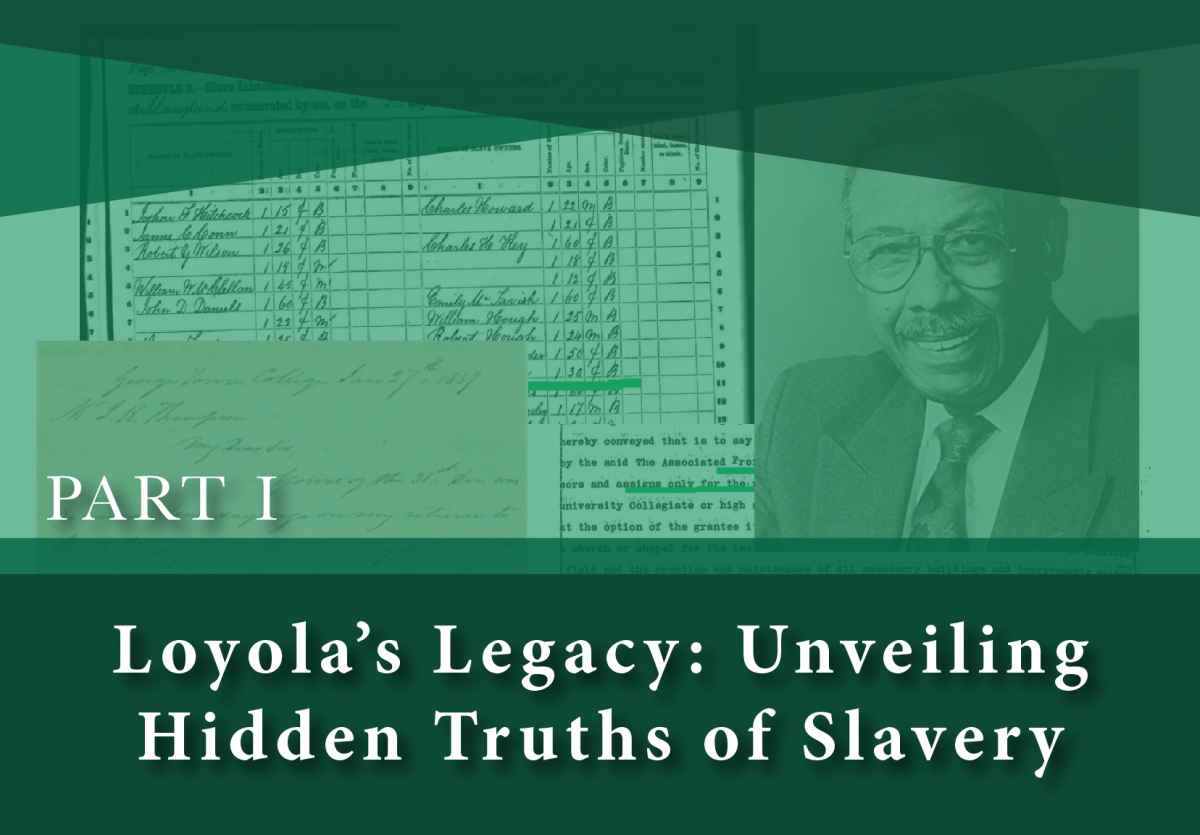

This article is the first of a four-part series investigating Loyola’s connections to slavery.

Would Loyola University Maryland even exist today without the sale of 272 enslaved persons through the Maryland Province of Jesuits? The answer is likely no, based on the research Loyola students and faculty have compiled during an investigation that began in 2021.

The President’s Task Force Examining Loyola’s Connections to Slavery released their 27-page report last January. The report shared many pieces of evidence that led to the conclusion of Loyola’s direct benefit from the purchase of enslaved individuals, facilitated by the province.

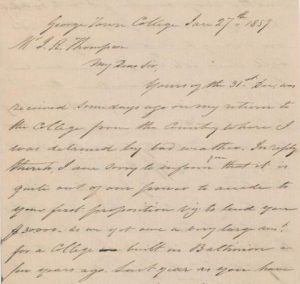

One piece of compelling evidence was an 1859 letter from the Maryland Province, a strong indication of Loyola benefitting from the sale of enslaved individuals and using profits to build the college. The letter addressed Mr. John Ryers Thompson’s request for an extension on his loan payment after purchasing enslaved persons from the sale. The province wrote back stating, “I am sorry to inform you that it is quite out of our power to accede to your first proposition viz: to lend you $30,000. As we yet owe a very large amt [sic] for a college built in Baltimore a few years ago.”

Students alongside Dr. David Carey Jr. and Loyola Notre Dame Library Head Archivist Jenny Kinniff discovered several other important pieces of relevant evidence that were included in the final report. Categories such as finances, attitudes, and labor were documented, as Kinniff highlighted.

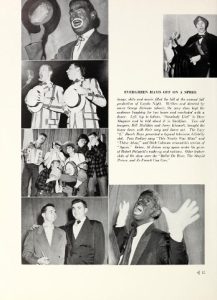

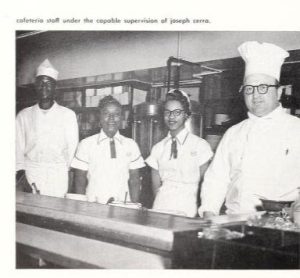

“We highlighted findings that shed light on the presence of racist attitudes on campus… such as blackface, odes to the KKK, and adopting gray as an official school color to recognize the Confederacy. We also uncovered documentation of Black workers on Loyola’s campus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Regarding racist attitudes, minstrel shows were hosted by the Loyola Drama Department. Student researchers found the evidence in the Evergreen Annual yearbook, with photos of students staged in blackface while performing. The photos may trigger emotional distress.

Another finding was the Loyola land deed of 1921 for the Evergreen property, stating that access to education was limited to “white persons.” This land deed was not updated until December 2020, according to Loyola’s Finance and Administration Treasurer John C. Coppola.

Director of the Office of Peace and Justice, Dr. John Kiess, spearheaded many of the initiatives and goals of the group.

“What we were examining were not just the connections to slavery at a particular point in history, but also how does that ripple into the future, what are the broader legacies immediately after emancipation into the early 20th century.”

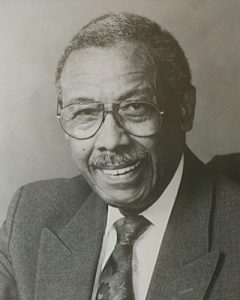

Charles H. Dorsey, Jr., ’57. Dorsey was the first Black full-time undergraduate student admitted to the college in 1949. He attended alongside several racial discriminatory practices, including the minstrel shows and the active land deed. Dorsey later went on to become the executive director of the Maryland Legal Aid Bureau and passed away in April 1995.

Kiess emphasized that there is more to be shared and resonate with when discussing the material.

“For me, what was so powerful was to hear task force members share their perspectives… to really hear the stories, hear the names of those who were involved in this history and to really see the human dimension of it.”

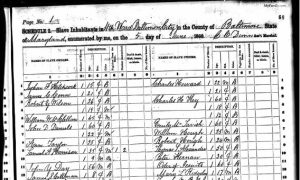

Another piece of evidence, the 1860 Census, is part of the documentation of the Order of the Jesuits in Baltimore using the labor of an unidentified woman listed as ‘enslaved’ on Loyola’s property. Additionally, Loyola’s first president John Early was documented to have rented “servants,” also another term for enslaved individuals of the 19th century.

Alongside this woman being omitted from history, White staff were named in the yearbook while Black staff in the same photo were not.

Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer Dr. Rodney Parker, emcee of the report launch, says he is proud of the task force and what is to come.

“I described my feeling at that time as ‘proud’ of Loyola for making public the history and committing to finding ways to work toward justice… I believe that this report can be the beginning of conversations and necessary actions to address historical ties to slavery and its legacies that even exist until this day.”

Loyola President Terrence Sawyer, who spoke at the launch, said, “We know that we cannot change the past. We must, however, understand the impact of sins and events of the past to be able to move forward. We must view history as it is, not as we wish it was.”

Alexis Faison is senior and a student representative of the President’s Task Force Examining Loyola’s Connections to Slavery, a researcher, and an editor of the upcoming book: Untold Truths: Exposing Slavery and Its Legacies at Loyola University Maryland. In her next article, she will explore conversations with two descendants of the GU272 sale.

A series of events are scheduled to further immerse students and communities in the research.